Made in 1953, this is a rare short film made by the influential husband and wife design team, Ray and Charles Eames. It portrays the communication theory developed by Claude Shannon in his book, The Mathematical Theory of Communications (1949).

|

A Communications Primer Made by Ray and Charles Eames 1953 |

|

1. Act or fact of communicating, as communication of smallpox, of a secret, of power. 2. Intercourse by words, letters or messages; interchange of thoughts or opinions. |

|

In the broadest aspects of communication, much work has recently been done to clarify theories and make them workable. The area we are entering might well be characterised as an area of communication. This film will touch in the most elementary way some aspects of the subject that are of daily concern to all of us. |

|

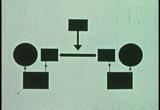

Here is Claude Shannon's diagram by which almost any communication process can be schematically represented. The information source selects the desired message out of a set of possible messages; the transmitter changes the message into the signal, which is sent over the communications channel to the receiver where it is decoded back into the message and delivered to the destination. Claude Shannon |

|

Every such system contains noise. Noise is the term used in the communications field to designate any outside force which acts on the transmitted signal to vary it from the original. In this usage, noise does not necessarily mean sound. Reading is a form of communication where the word is a signal, the printed page the transmitter, light the channel, the eye the receiver. Here sound can act as noise and interfere with the message. But in some situations, like reading on a train, where the sound level is normally high, it is not the sound that interferes with the communication process as much as the motion and the unpredictable quality of the light source. Quality of light and motion then become noise. In radio, noise could be static. In television, noise is often the distortion of the picture through transmitting or receiving. In a typewritten message, the noise source could be in the quality of the ribbon or the keys, and we are all familiar with the carbon copies that keep getting progressively worse. If anything acts on the signal so as to bury it in an unpredictable and undesirable way in the communications system, it is noise. |

|

We can consider telegraphy in terms of this same diagram. We will use a New York stockbroker's office as the information source and a Los Angeles stockbroker's office as the destination. There may exist at the information source just two possible messages, BUY or SELL. From these two, the message SELL is selected, then coded by the telegraphic transmitter, then sent over the channel in electrical impulse signals, decoded by the receiver back into the message SELL, and delivered to the destination. Noise of course is there, this time acting electrically. It could distort the signal in such a way as to change SELL into SELF, but as there are only two possible messages, BUY and SELL, there is sufficient redundancy in the spelling of the words that even if it did read SELF, the information would still be clear. Naturally, this example has nothing to do with the stockbroker's office of today, because of all organized communication, market information is perhaps the most efficiently handled. The New York information enters the signal channel in this form and is automatically decoded in Los Angeles in this form. But even here we find redundancy counteracting noise. The English language is about one-half redundant. This extra framework helps prevent distortion of the message in the written language or in the spoken language. |

|

In speech, the brain is usually the information source. From it the message is selected - the messages of thought, not the words. The vocal mechanism codes the words into vibrations and transmits them as sound across the communications channel, which is of course the air. The sound of the word is the signal. The ear picks up the signal and with the associated eighth nerve decodes the signal and delivers the message to the destination. This time, noise could originate in the transmitter or in sound vibrations that disturb the channel. Or it could be a nervous condition on the part of the receiver and it could change the message from I LOVE YOU to I HATE YOU. How do you combat it? One way is through redundancy - I LOVE YOU, I LOVE YOU, I LOVE YOU. Another is increasing the power of the transmitter; this combats noise, as does the careful beaming of the signal, or duplicating the message via other signals. |

|

Now let's consider amount of information communicated. The message SELL contained one bit or unit of information because it was a choice of two possible messages, BUY or SELL. A choice of two gives one bit of information. This is the amount of information that one on-off circuit can handle at one time. It can be on or off. Two bits of information is the amount two circuits can handle. There is a choice of four possible conditions: on-off, off-on, on-on, or off-off. Three circuits can handle three bits, or a choice of eight possibilities. Four circuits, four bits, or 16 possibilities. Five bits, 32 possibilities. Six bits, 64. Amount of information increases as the logarithm of the number of choices. The message I LOVE YOU, to communicate information, must also be a choice of other messages, because if the information source were so loaded with feelings of love as to be incapable of any other thought, then surely by the time the words I LOVE YOU were spoken, no information was communicated at all. No information; yet previous experiences could make those three words convey great meaning. |

|

Source, message, transmitter, channel, message, destination. You could imagine the message being music and the transmitted signal being tone, or it could be applied equally well to writing, or to smoke signals, or to hand signals. But let's take painting as another example of a signal transmitting a coded message. Information source, mind and experience of painter. Message, his concept of a particular painting. Transmitter, his talent and technique. Signal, the painting itself. Receiver, all the eyes and nervous systems and previous conditionings of those who see the painting. Destination, their minds, their emotions, their experience. Now in this case, the noise that tends to disrupt the signal can take many forms. It can be the quality of the light, or the colour of the light, or the prejudices of the viewer, or the idiosyncrasies of the painter. But besides noise, there are other factors which can keep the information from reaching its destination intact. The background and conditioning of the receiving apparatus may so differ from that of the transmitter that it may be impossible for the receiver to pick up the signals without distortion. |

|

In any communication system, the receiver must be able to decode something of what the transmitter coded, or no information gets to the destination at all. If you speak Chinese to me, I must know Chinese to understand your words. But even without knowing the Chinese language, I can understand much of your feelings through other codes we have in common. There are systems of communication where there is no redundancy and no duplication of the message. Here knowledge of the code is essential. In planning 'One if by land, two if by sea', the fellow on the opposite shore simply had to know the code. But there are also many examples of times when the message has been conceived and the signal sent long in advance of understanding or acceptance of the code employed. In the case of Galileo or Socrates, it did not in time matter that the receivers of their time were not tuned to receive their signal. The ultimate transmission of such a message represents communication of a very complex order. Other high-level communication occurs in very different areas. A wave breaking on a beach brings a world of information about events far out at sea. It can tell of winds and storms, the distance and the intensity; it can locate reefs and islands and many things if you know the code. |

|

When we watch them turning and wheeling, how often have we wondered what holds such birds together in their flight? Communication is that which links any organism together. It is communication that keeps a society together, and though these people seem unaware of each other's existence, neither looking nor speaking, one group meets and filters through the other with hardly two individuals coming in contact. So constant is the flow of information and so complex the web of communication that keeps them apart and holds them together. |

|

The symbol - the abstracting of an idea, communication at once anonymous and personal. Personal because of the countless individuals that created its form, each one who in his turn added something good or who took something bad away. Anonymous because of the numbers of individuals involved and because of their consistent attitude. These are examples of communication of an idea through symbols. But there can also be communication through symbols to an idea, as in the burnt offering or in the flame of a candle. The use of flame as a transmitter in the communications channel is probably as old as man's first fire. It stands for all the wonder and mystery of forces beyond man's knowledge. The storm warning flags are part of a long, evolutionary tradition of symbols, but their beginnings were probably in basic reactions to colour and form, basic enough to make their communications carry beyond the barriers of language and custom. But symbols also change and evolve. Some methods of transmitting messages rapidly become symbols, then pass into obscurity to become readable only to the anthropologist, while other symbols of communication remain. |

|

The message being transmitted here may be unlimited in the range and subtlety of its ideas yet the method and the signal are such that they must be fed to the transmitter in a series of positive decisions. The system calls for the key to be either up or down. The code calls for a dot or a dash. The current flows, it ceases to flow, it flows. It is black or white. It is STOP or GO, on or off, one or none, go or no go, or black or white as in this small area from a half-tone reproduction in a magazine. The press that printed it is capable of printing but one colour of ink at a time, in this case black ink on white paper. In order to transmit the image, it had to be broken down to many points of decision, black or white. We know that such a limitation is not at all restricting if enough decisions are made. In this case, half a million decided points give a fair rendition, a million would be better. Conventional printing of colour is no different, except that with the added factor of colour, four times the number of decisions have to be made, one set in yellow, one in red, in blue and in black. |

|

Whenever added factors in a problem are recognised, the number of decisions necessary for the solution grows by large leaps. As theories and equipment and men develop, it becomes apparent that one sure way of handling multiple factors is to build a system that can handle each decision in its time. Men have long known the theory on which complex problems of many factors can be solved, but the number of decisions, the calculations necessary were prodigious. Not until the recent development of the electronic calculator could these areas be touched. The problem became one of communication between man and machine, between machine and machine, between machine and man. The cards are punched or not punched, light passes or stops, and by this binary system, information is fed to the machine. In a moment, we will hear sounds which are an actual product of a huge calculator. The frequencies are made audible to check its functioning and, in a way, feel its pulse. Here it is. |

|

The ability of these machines to store information, manipulate, sort and deliver it, is fantastic, and with their complex feedback systems, their memories, their almost human reaction to situations, it is understandable that they are popularly referred to as 'brains'. The greatest fallacy in the comparison is one of degree. The decisions made by the machines are comparable in number to the half-million in this half-tone, but far greater are the number of stops and goes performed by the human nervous system in order to complete the simplest act. So great that if each decision were represented by a small half-tone dot, the total area of dots would cover several Earths. Such is the magnitude we reach when a number like a half-million is raised to the fourth power. |

|

As flowing as the human movements may seem, they are actually the product of these countless yes/no decisions communicated with great speed to and from all parts of the body. The channel is the nervous system. Each nerve is made up of hundreds of fibres. The decision is the impulse of a single nerve fibre, an all-out event, a trigger process which is set off like an explosion when the stimulus exceeds the ignition point. The dot in the half-tone, the hole in the tape - each is a separate fire/no-fire signal, but together they add up to a smooth, sometimes incredibly complex action that often seems more vague than decisive. Yet many things that we accept as undecided vagaries would be, if we could bring our focus in sharp, decisive individual units. It is the responsibility of selecting and relating parts that makes possible a whole, which itself has unity. |

|

The line on which each colour breaks, and the point at which each dot that makes up this painting is placed, affects the whole canvas. The communication of the total message contains the responsibility of innumerable decisions made again and again, always checking with the total concept through a constant feedback system. These elements of a communications system act together as one great tool, and though the tool may perform complex tasks, it will never relieve the man of his responsibility, no matter where it occurs, no matter what the technique. Communication means the responsibility of decision, all the way down the line. |

|

Credits and acknowledgements |

More about this film

LOOP: AIGA Journal of Interaction Design Education, April 2001

ArtForum, October 1999

More about Ray and Charles Eames

Eames Exhibition at Library of Congress

Filmography